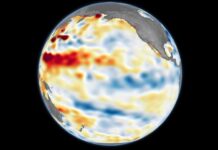

In the vast, icy expanse of Greenland, a fascinating interaction is occurring between retreating ice sheets and the tiny organisms that inhabit the surrounding ocean waters. This intriguing phenomenon has captured the attention of scientists and researchers who seek to understand the complex dynamics at play. A recent study, supported by NASA, has thrown light on this subject by examining how the meltwater from Greenland’s ice sheet is contributing to the growth of phytoplankton, a crucial component of the ocean’s ecosystem.

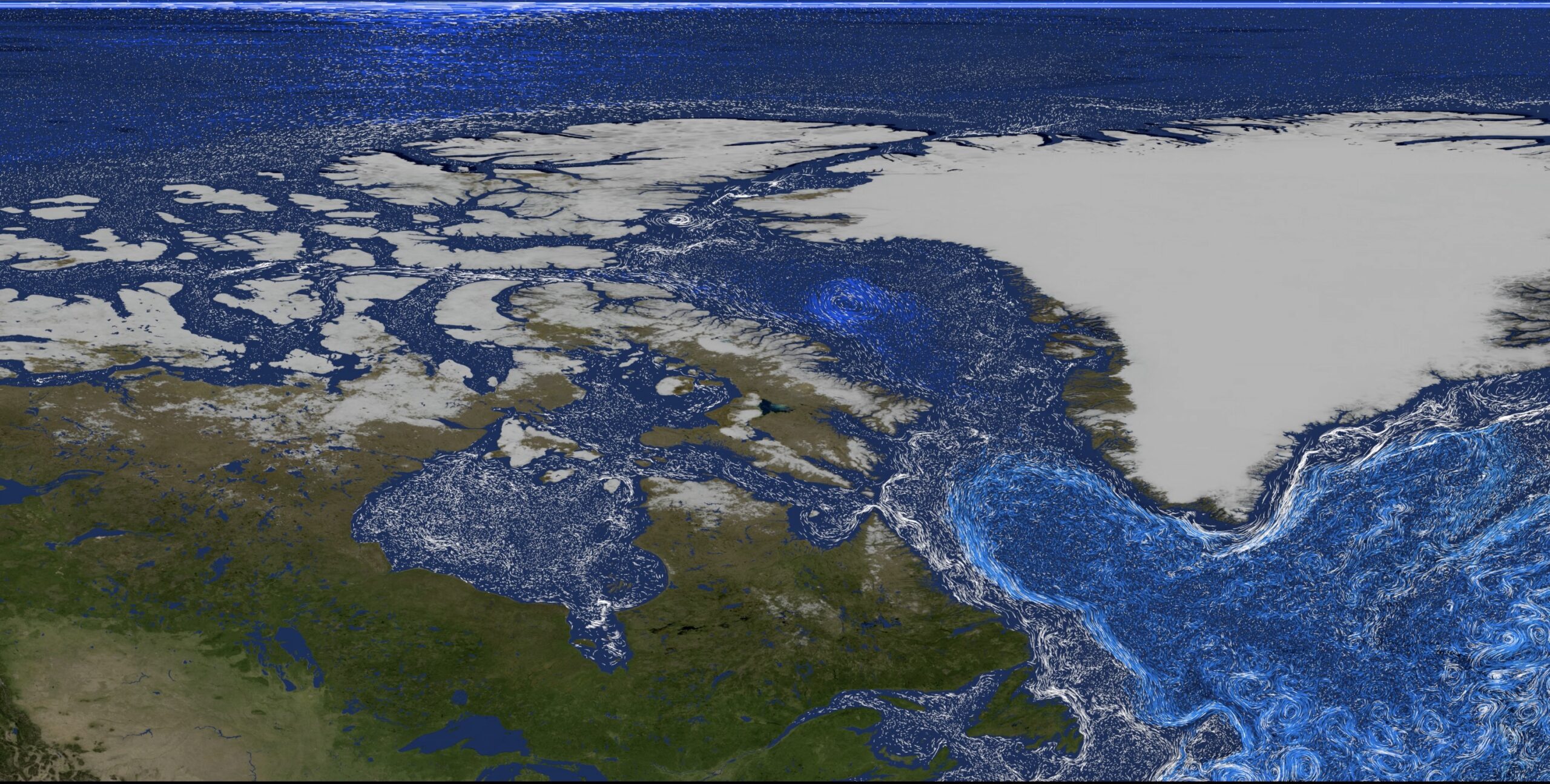

To unravel the mysteries of this interaction, scientists employed advanced computer modeling techniques developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). These models serve as a virtual laboratory, allowing researchers to simulate and study the intricate processes happening in the waters around Greenland’s glaciers. The findings of this study were published in Nature Communications: Earth & Environment, highlighting the role of nutrient-rich runoff in boosting phytoplankton growth.

Every year, Greenland’s massive ice sheet is shedding approximately 293 billion tons of ice. This enormous volume of freshwater, during the peak summer melt, drains into the ocean at a staggering rate of over 300,000 gallons per second from beneath Jakobshavn Glacier, known locally as Sermeq Kujalleq. As this meltwater mixes with the ocean, it initiates a fascinating process: the less dense freshwater rises through the saltier ocean water, potentially bringing essential nutrients like iron and nitrate to the surface where phytoplankton reside.

Phytoplankton, despite their minuscule size, play a colossal role in the marine food chain. These tiny plant-like organisms absorb carbon dioxide and serve as a primary food source for krill and other small marine creatures, which in turn support larger animals such as fish and whales. The growth of phytoplankton is thus a fundamental part of the oceanic ecosystem, impacting everything from carbon cycling to fisheries.

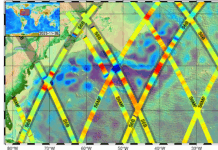

Previous analyses using NASA’s satellite data have revealed a remarkable 57% increase in phytoplankton growth in Arctic waters from 1998 to 2018. This surge is partly attributed to the nutrient influx from glacial meltwater, especially during the summer months when other nutrients are depleted following spring blooms. However, conducting direct observations in Greenland’s remote and iceberg-laden waters posed a significant challenge for scientists.

To overcome these challenges, the research team turned to state-of-the-art computer modeling. As explained by Dustin Carroll, an oceanographer at San José State University and affiliated with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a sophisticated model was essential to understand this remote and dynamic system. The team utilized the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean-Darwin (ECCO-Darwin) model, a comprehensive ocean simulation tool that integrates a massive amount of oceanographic data collected over the last three decades. This data includes parameters like water temperature, salinity, and seafloor pressure, providing a detailed picture of the ocean’s conditions.

Michael Wood, the lead author and a computational oceanographer at San José State University, described the modeling process as a “model within a model within a model.” This approach allowed the team to focus on specific areas, like the fjord at the glacier’s foot, providing insights into the localized interactions between biology, chemistry, and physics. By leveraging supercomputers at NASA’s Ames Research Center, the researchers calculated that nutrients lifted by glacial runoff could enhance summertime phytoplankton growth by 15 to 40% in the study area.

The potential implications of increased phytoplankton growth for Greenland’s marine environment and fisheries are profound, though the full ecosystem impacts will require further investigation. The melting of Greenland’s ice sheet is expected to accelerate in the coming decades, influencing sea levels, coastal salinity, and land vegetation.

Carroll emphasized the importance of extending these simulations beyond the initial study area to encompass Greenland’s entire coastline, which hosts over 250 glaciers. Such efforts will enhance our understanding of the broader ecological and climatic effects of glacial meltwater.

The study also explored the dual impact of glacial runoff on the carbon cycle. While the altered temperature and chemistry of seawater in the fjord reduce its ability to absorb carbon dioxide, this effect is counterbalanced by the increased phytoplankton blooms that absorb more carbon dioxide during photosynthesis.

Wood highlighted the versatility of the modeling tools, stating that they are not confined to a single application. Like a Swiss Army knife, these models can be adapted to study various regions and scenarios, from the Texas Gulf to the waters of Alaska.

This study not only sheds light on the intricate interactions between Greenland’s glaciers and the ocean but also underscores the importance of advanced modeling techniques in understanding our planet’s complex systems. As the ice continues to retreat and climate patterns evolve, such research will be crucial for predicting future changes and managing the impacts on marine life and global ecosystems. For further details, the original publication can be accessed through the Nature Communications: Earth & Environment journal.

For more Information, Refer to this article.