In July 1969, history was made when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took humanity’s first steps on the Moon. Fast forward to the present, NASA, along with its international collaborators under the Artemis Accords, is making strides to return humans to the Moon, this time with the intention of establishing a more permanent presence. However, the journey is fraught with challenges, including one unexpected adversary—the Sun.

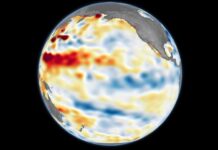

The Sun is a powerhouse of energy that sustains life on Earth. Yet, it also poses significant risks. On Earth, these risks can range from something as minor as a sunburn to severe disruptions in our satellite systems caused by geomagnetic storms. The complexity of dealing with solar energy increases significantly when we venture into space.

On Earth, we are shielded by our atmosphere and magnetosphere, which act as barriers against most of the Sun’s harmful energy. However, spacecraft and astronauts do not have this luxury of protection in the void of space. For astronauts embarking on the upcoming Artemis missions to the Moon, exposure to the Sun’s radiation could lead to dire consequences—damaged electronics or an increased risk of cancer over time.

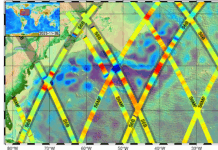

A historical precedent of the Sun’s volatile nature was the massive solar storm that erupted on August 2, 1972, from sunspot MR11976. This storm produced one of the fastest-recorded Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), which traveled from the Sun to Earth in under 15 hours—a record that remains unbroken. The storm caused significant disturbances, including power grid fluctuations and issues with spacecraft operations. Notably, recently declassified U.S. military records revealed that this storm was potent enough to trigger the explosion of sea mines off the coast of Vietnam.

This solar storm occurred between the Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 missions, and research indicates that had it coincided with a lunar mission, astronauts could have suffered severe radiation sickness. This threat persists; a solar storm of such magnitude could pose a similar risk during future lunar expeditions.

To mitigate such risks, organizations like NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) continuously monitor solar activity to predict potential hazards. By tracking solar flares and CMEs, scientists aim to provide advance warnings, allowing for protective measures to be implemented. For astronauts on lunar missions, this might involve seeking shelter in specially designed areas of their spacecraft.

NOAA’s Space Weather Follow-On (SWFO) program is a critical component of this monitoring effort, providing essential space weather observations and data. Instruments such as the CCOR-1, launched aboard the GOES-19 spacecraft, deliver vital near-real-time CME data. Future plans include the deployment of the CCOR-2 instrument on SWFO-L1. Additionally, collaborative missions like the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a partnership between NASA and the European Space Agency, and NASA’s HERMES instrument, intended for the lunar Gateway, contribute to our understanding of solar phenomena.

NASA’s Moon to Mars Space Weather Analysis Office (M2M SWAO) plays a crucial role in real-time space weather assessments, enhancing our ability to predict and react to space weather impacts on exploration activities, including those on the Moon.

The drive to return to the Moon is fueled by the potential wealth of information it holds about the Solar System’s history. “Every object in our solar system is in constant interaction,” explains Prabal Saxena, a Research Space Scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The Moon, with its numerous impact craters, bears testament to these interactions, not only with meteoroids but also with the Sun.

Saxena highlights that the Moon’s lack of a magnetosphere makes it a repository of solar history. “The surface material on the Moon captures energetic particles that Earth’s magnetosphere and atmosphere would otherwise deflect. This allows us to trace back and understand the Sun’s historical behavior,” he states.

This is analogous to how scientists study ice cores to glean insights into Earth’s atmospheric history. The Moon’s surface, largely undisturbed for millennia, holds clues to everything from the ancient solar atmosphere to the Sun’s effects on lunar water, underscoring the importance of further exploration.

However, it is vital to remain vigilant about the potential threats to both human explorers and their equipment. In a reflective conversation, Lennard Fisk, former NASA Associate Administrator for Space Science and Applications, recounted a discussion with Neil Armstrong. Armstrong expressed his greatest fear during the Apollo 11 mission was not technical failure but an unpredictable solar flare—a stark reminder of the uncontrollable variables posed by space weather.

Our understanding of space weather has evolved dramatically since 1969. Back then, the notion of space radiation, including the solar wind, was relatively new. Nonetheless, early research laid the foundation for discoveries that continue to yield benefits today. We are building on these findings with innovative missions that enhance our knowledge of the Sun and our solar system.

In conclusion, as we look forward to the next era of lunar exploration, understanding and mitigating the risks posed by solar activity is crucial. By leveraging advanced technology and international collaboration, we aim to ensure the safety and success of humanity’s return to the Moon, unlocking the secrets it holds and paving the way for future endeavors beyond our planet.

For more Information, Refer to this article.